When cooking a whole hog, you need to learn a few ancient techniques.

Our ancestors lacked refrigerators, and needed to get a bit more creative to make sure a couple hundred pounds of meat remained bacteria-free until they mowed it all down.

Today, there are few cuts of pork you just throw straight into a pot or pan. More often you’ll do something to make it last longer, usually a combination of salting, smoking, and/or covering in rendered lard.

Although we now have reliable refrigeration, these methods live on since they also make the meat much tastier.

And the most fundamental food technique of all is salting.

The Trials and Tribulations of Salt

Although we think of salt first and foremost as a flavoring ingredient, it was primarily used by early humans for its ability to keep food from rotting.

Salt draws out water from foods, which is what bacteria thrive in. This creates an environment that is hostile to the proliferation of the nasties that cause foodborne illness.

It just so happens that the loss of water concentrates flavors, the salt enhances flavors, and left to sit long enough, the salt can cause fermentation that results in completely new flavor compounds.

Salting can also denature the proteins on the surface of the meat, which allows it to hold more liquid in as it cooks.

(This helps to minimize overcooking of the outer layers of the cut, resulting in a juicy center no matter how much you sear the outside.)

Tools of the Trade

Brining, curing, and fermenting are simple skills that are unfortunately neglected by most modern home cooks, but learning how to do them properly will bring your craft to a new level.

And fortunately, you won’t need much more than what you’d typically need for a minimalist kitchen.

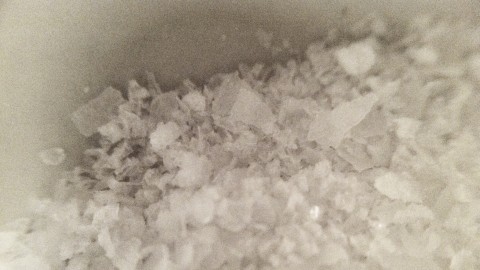

Kosher salt is one of the most useful ingredients you can keep on hand in your kitchen, and is great for making brines.

Since you’ll be going through a lot of salt, it pays to have something economical, and the kosher variety fits that bill.

It’s also the main salt you should be using in the kitchen, since it is easy to measure by hand and (usually) bereft of things such as iodine or anti-caking agents that really have no business being in salt.

The one problem many people have with kosher salt when making wet brines is that the large crystals take longer to dissolve.

It’s generally suggested that you then either use smaller-grain table salt or pickling salt, or heat up the water to dissolve… before letting it cool down again before adding any food.

My experience has been that this advice is needlessly complicated. Heating water up only to cool it down takes forever, and I’d rather not keep too many ingredients in my kitchen if I don’t have to.

I’ve found that stirring kosher salt into water works just fine in creating a brine. Just make sure to stir it well and let it sit until the liquid turns clear (should be no more than 15 minutes).

Curing salt, not to be confused with pink Himalayan salt, is a type of salt that is crucial to curing meat.

It contains 6.25% nitrite, which helps to kill off more microbes in meat that is brined and then smoked.

It also imparts a pink color to the meat. And while the bacteria-killing abilities of nitrite are worth noting, modern standards of food safety mean we use it primarily to make sure our ham and bacon have a nice pink color.

The salt is dyed pink in order to prevent anyone from accidentally using large quantities of it, which can be poisonous.

Curing salt should only, ever, be used in very small quantities, and only when curing meat.

Sugar is often employed in brines to offset the harshness of the salty flavor.

But sugar doesn’t penetrate the meat the way that salt does, and if you are washing the meat after curing then you may very well be washing all the sugar off as well.

That being said, you might want to add in some sugar forthehellofit anyways, particularly if you are making bacon.

Your choices for sugar are endless here. White sugar, brown sugar, natural sugar, molasses, and maple syrup all are good candidates for brine, and all bring their own flavors to the table.

Spices, herbs, and aromatic vegetables are another typical addition to brines, but I’m even less convinced that these do anything to the meat cured in wet brines.

They might be more useful for the more concentrated dry brining used for bacon and other charcuterie, but you should experiment for yourself and be the judge.

Cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice, coriander, juniper, and peppercorns are ideal brining spices. For herbs, try thyme, parsley, bay leaves, or sage. Vegetables such as garlic and onions should work well, too.

A balance is most useful for baking, but can be helpful for brines as well.

Different brands of salt and sugar will have different densities, so using the traditional method of measuring volumetrically with cups won’t give you exact or reproducible results.

A good digital balance is missing in most home cook’s kitchens, but it will be one of your most-used tools if you can pony up the modest amount to get one.

Mixing bowls and food storage bags are necessary for mixing up brines and storing meats during curing.

Mixing bowls are used for preparing brines (and doing any short brine of less than a few hours).

Gallon-size Ziploc bags may cut it for curing bacon, but you’ll need something bigger for the ham and hocks.

Ziploc makes huge food-grade plastic bags that fit the job here. You can also look for other brands (as long as you are sure they are food grade!) or use rigid plastic containers instead.

Basic Dry Brine

A dry brine, at its most basic, means adding dry salt to meat. That’s it.

This technique is most useful for:

- Whole chicken and other poultry, which gets crispy skin as the result of the drying effects of the salt.

- Steaks, roasts, and other fatty cuts that you hope to brown on the outside while remaining juicy on the inside.

To make a basic dry brine… well, you don’t really make it. You just sprinkle salt over the meat at least an hour before cooking.

I won’t be using any basic dry brine for the whole hog project, since all lean cuts will be wet brined, and the parts I use for curing will require pink salt.

Basic Wet Brine

Dry brining can be a fast and simple way to get the benefits of brining meat, but lean cuts such as fish and skinless poultry require something a little different.

Instead of sprinkling salt directly on the meat, you first create a solution in water to submerge it in.

The ideal brine is somewhere between 5% and 8% salt by weight, but since you are just giving your food a quick plunge, exact measurements aren’t really necessary here.

For a quick and dirty basic wet brine, just stir together until dissolved:

- 1 cup (250 mL) kosher salt

- 1 gallon (4 L) water

If you feel like breaking out the balance, aim for the following weights:

- 250 g salt

- 4,000 g water

For the whole hog project, I will use the basic wet brine for pork chops and tenderloin (since they are so lean and prone to drying out) and also for soaking the head and trotters before making headcheese (just for shits and gigs).

Dry Brine for Curing

Using some plain ’ol salt for dry brining works fine if you are simply preparing a steak or roast for cooking in a couple hours, but what if you are looking to preserve and cure a piece of meat, such as pork belly?

In these cases, nitrites were traditionally added into the mix in order to ensure the death of nasty microbes.

It also had the benefit of adding a pinkish hue to these meats, which is the main reason we use it still today.

Many people suggest using sugar in brines to balance the harshness of the salt, and I think that it’s most useful for dry curing brines.

Since the only liquid your brine will be dissolving in is getting pulled from the meat, it ends up sitting in a more concentrated solution, which is more likely to flavor the exterior of the meat.

Michael Ruhlman suggests a dry brine composed roughly as follows:

- 6 parts kosher salt

- 3 parts sugar

- 1 part curing salt

All measures are by weight, and I’d definitely suggest using a balance, since you want to make sure you don’t use too much curing salt.

You can add herbs, spices, aromatics, etc. into the brine as well here.

Dry curing brines are good for really fatty cuts, and I’ll be using it to make bacon.

Wet Brine for Curing

We use wet curing brines for relatively lean cuts of meat, and/or large pieces that we will be brining for a long time.

The quick and dirty method is to just add about 70 parts water by weight to the same dry curing rub you created, so:

- 6 parts kosher salt

- 3 parts sugar

- 1 part curing salt

- 70 parts water

In more practical terms, this amounts to:

- 300 g kosher salt

- 150 g sugar

- 50 g curing salt

- 3.5 L (3.5 kg) water

I highly recommend using a balance here as well, so you make sure your brine is strong enough to preserve your food.

I will be using a wet curing brine for the hams and hocks before smoking them.

Hitting the Rock

Salt is the only rock humans eat.

It’s impossible to understate the importance that sodium chloride has played in the development of cooking, and it’s a shame that it has come under so much fire recently.

Salt is an essential nutrient. It allowed us to keep our food edible longer. And it made everything tastier.

The tradition of using salt to preserve meat is nowhere more evident than the spectrum of classic pork preparations that utilize it.

And I sure as hell will be making the most of it during the whole hog project.

I'm a science geek, food lover, and wannabe surfer.

I'm a science geek, food lover, and wannabe surfer.

Comments on this entry are closed.