We humans like things to be straightforward. Black and white, with no shades of gray. To conform with the traditional theories of logic that trace back to Aristotle.

But in real life, we can only wish to be so lucky.

Try as we might to make rational sense of the world we live in and boil it down to a few simple equations, to label everything as inherently good or bad, this simple yet lofty goal continues to escape the most brilliant of thinkers.

For every great scientific discovery, another proves itself hopelessly flawed and is ultimately abandoned. What’s more, our efforts to understand the world around us often end up in the realization that the universe is governed just as much by paradoxes as it is by neat mathematical formulas.

The world of health and fitness is particularly susceptible to the kind of overly-cocky theories that tend to take hold of the public’s mind, even though a closer inspection finds them to be sorely lacking in both the realm of logical integrity and real-world applicability.

Although it’s crucial to take a scientific approach to health and fitness, it’s important to not take too seriously the sensational headlines that elbow their way onto the main page of news websites, and instead focus on finding out works for us as individuals.

The Earth, the Sun, the Controversy

When you think about it, it’s unsurprising that most people thought that the Earth was at the center of the universe. After all, wouldn’t we feel it move if it wasn’t?

But this “earth-centered” model was in trouble from the outset. If the Earth was really at the middle of it all, then how come all the other planets appeared to be at different distances from us throughout the year?

So astronomers started adding more complexity to the theory. Instead of being at the exact center of the universe, it was actually slightly off-center.

And instead of simply orbiting the Earth, the planets also orbited their orbits, in much the same way that the moon orbits the sun, but also orbits the Earth on top of that. These extra orbits were known as epicycles.

But even that wasn’t enough, so these astronomers found that they could get more and more precise by adding more and more epicycles.

Nicolaus Copernicus started the fire that would eventually led to the scientific consensus shifting to the sun-centered model in 1543, when his “On the Revolutions of Heavenly Spheres” was published.

But it took nearly 200 years for this idea to become commonly accepted, and needed the help of such geniuses as Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton.

If Kanye West Was a Scientist, He’d Fit Right In

This phenomenon of “adding epicycles” is endemic in the modern health and fitness world, where people aggressively argue that fat is bad, that carbs are bad, that meat is bad, or that starches are bad, despite these theories not quite fitting with observations that people eating these foods are quite often in excellent health.

This is perhaps most evident in the low-fat diet fad that has been going strong since the late 70s/early 80s. The seeds of this revolution were sown by Senator George McGovern, whose 1977 report “Dietary Goals for the United States” strongly influenced governmental dietary guidelines, which then spread to private nutritionists and the rest of the world in general.

Since then, an unbelievable amount of studies have been published criticizing fat, especially saturated fat, and cholesterol.

But, Lucy, we got some prooooooblems here.

First and foremost are the overwhelming observations that many populations and individuals eat a high-fat diet and are doing great. Not only that, but a low-fat diet, particularly when it is low-calorie, is notoriously difficult to follow.

But the tide is slowly turning against low-fat. People are increasingly abandoning their Snackwell’s cookies en masse and looking for an easier way to look and feel better. This is happening at a grassroots level, as the government isn’t budging on their recommendations, which is who most mainstream nutrition experts look to for validating their advice.

The first place that many people are going to is the low-carb side. If fat is good, then carbs must be the REAL problem, right? Well, this theory is riddled with all the same holes that the low-fat paradigm is. There are just too many people in the world doing just fine thankyouverymuch on high-carb diets to just jump to the conclusion that those little CHO chains are really the problem.

The next place people end up is in the low-calorie camp. On paper it makes sense. All that it really comes down to in weight management is energy balance. Calories in, calories out. But the problem with this is that it is demonstrably impossible to count and manipulate the calories entering and leaving your body in a way that you could realistically affect (weight) change.

Okay, so perhaps you could just eat very little and exercise a ton, which is a more realistic but less accurate way to incur a caloric deficit. But the metabolic issues this causes can only lead to problems in the long run, which usually isn’t a problem because your body will fight against artificially-imposed caloric deficits the same way it will fight against being held underwater and deprived of oxygen.

Ouch!

Embracing Uncertainty–Magic Bullets vs. Big Wins

There are no simple answers when it comes to losing fat, gaining muscle, and reducing illness and injury.

People who blame fat, carbs, calories, or any other singular nutrient are offering up “magic bullet” solutions, wherein altering your consumption of one of these things will magically help you attain all your health and fitness desires.

They often work at first–as diets often do–helping you lose weight and look better, but most people will eventually fail at them. This is because diets are inherently difficult to follow, and the more you deprive yourself the harder it will be to stick with it. It all comes down to all the willpower you end up burning in the process.

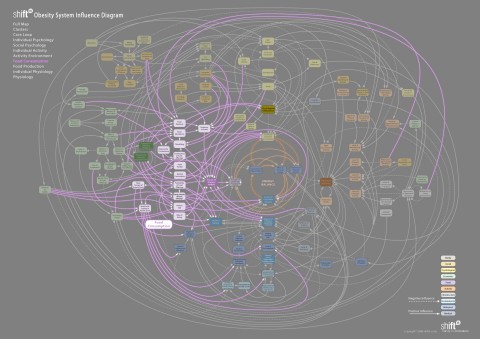

Ultimately, your health and fitness are dependent on an unbelievable amount of variables. Here’s an excellent image showing many of these factors and how they are interrelated.

Holy hell! Did you see all that? How can we conceivably fix all those variables so that we can get our physical health in order? How can we keep track of everything?

Focus on “big wins.”

We take a different approach to the “magic bullets” perspective around here. Instead of looking at singular things that we think will solve EVERYTHING for EVERYONE, we look instead for singular things that we think will solve ALMOST EVERYTHING for ALMOST EVERYONE.

In other words, we focus on BIG WINS rather than MAGIC BULLETS.

Will they work for everyone? No, and I admit that. But chances are it will work better than anything else.

By embracing uncertainty like this, we are able to more honestly assess what works and what doesn’t, and by not placing all our eggs in one basket, we can take a more realistic approach to improving our health and fitness.

There are three main tools that we have in determining what will best support our health and fitness:

- Observation–Looking at what has worked for large populations.

- Isolation–Isolating variables in randomized populations.

- Self-experimentation–Trying things out yourself and keeping track of the results.

Each is incomplete in and of itself–it has a certain level of uncertainty that must be accepted. But taken together as a whole, you can easily find the big wins–or the little changes that make a big difference for YOU.

Observation–An Excellent Foundation

One of the most common arguments against meat eating are observations of say, China or war-torn Norway. As compelling as it is to learn that those Chinese that eat more eat suffer from more cancer, it’s important to not let this kind of thinking drive your decisions too much.

One such example comes from the “power line scare” that originated with a 1979 paper by Nancy Wertheimer and Ed Leeper, who published an observational study that showed that those who lived close to power lines had a higher incidence of cancer than those who didn’t.

The New Yorker picked the story up and started a large-scale fear of power lines. But over time, this hypothesis was tested more rigorously and found to be utterly false.

This isn’t to imply that observation has no merit. It does. But its power only really reveals itself when you look at it globally, as opposed to selected groups cherry-picked to support your initial hypothesis.

Perhaps the most influential of people when it comes to global patterns of healthy diet was Weston A. Price. He spent many years traveling everywhere from Alaska to Sub-Saharan Africa to the South Pacific, and a great summation of his findings on the patterns of healthy people he found can be found in his essential book “Nutrition and Physical Degeneration.”

Where Dr. Campbell restricted his observations to a part of the world that just so happened to conform to his world view that animal products=bad, Dr. Price found many populations living on meat-heavy diets to be examples of perfect health.

This isn’t to say that vegetables or carbohydrates are bad, either. From the potato- and corn-consuming cultures of Central and South America to the rice-chowers of Eastern and Southeastern Asia, anyone arguing that these things are bad for you have no real leg to stand on.

From observations of modern healthy cultures as well as approximations of the preagricultural human diet, we can see that humans run best on animal fat, plant starch, or a combination of the two.

Fat is fine. Carbs are cool. Meat is amazing. And potatoes are terrific. There’s too many observations out there that suggest this is true to deny. Don’t let the outliers convince you otherwise.

Isolation–The Next Step

When I was in grade school, one of my biggest frustrations was that I always heard about these new scientific findings on the evening news but never heard about them during class. The things Tom Brokaw was telling me seemed to be more important than the minutiae that I was learning at school.

I learned years later that this was probably a good thing.

Despite its reputation as a perfect progress from chaos to order, the history of science shows that it moves in fits and starts, often stalling out in completely false paradigms for a long time.

In other words, the scientific studies that make the headlines often have little to do with scientific progress in general, and often prove to be completely wrong upon further scrutiny.

This can be seen in everything from the paradigm shift of the Copernican Revolution, as I explained above, to the paradox of Schrödinger’s Cat.

Now, I don’t mean to slag on science here. I am an analytical chemist by education and spend my days in a lab coat and goggles running and analyzing samples for a biofuels company. I’m a total science geek, and think it is one of the most powerful tools we humans have.

But I’m no longer satisfied that it is able to efficiently describe everything. Although we scientists don’t like to admit it, sometimes a bad study slips through… and sometimes MANY bad studies make it out.

If you pay any attention, you’ll see that there are studies out that both condemn and praise nearly EVERY nutrient that has yet been identified.

Ultimately, the biggest problem with much of scientific discovery when it comes to health and fitness is its insistence in seeing the world in such a cut and dry way.

It’s important to remember that every food source–with the exception of dairy and fruit–doesn’t “want” to be consumed.

By that I mean that all other organisms on the planet are bound by the same unyielding laws of evolution as we are. We tend to see plants as “purer” than meat and believe that it is a less cruel way to satiate our caloric needs.

But plants have no desire to be eaten. Many of them produce fruit in the hopes that animals will eat it and then spread their seeds, but it does them little good if they eat their stalks or roots as well, thus killing these plants.

And so many of them evolve anti-nutrients in order to block absorption and drive their predators away. Since they aren’t able to run away from anyone trying to eat them, they have to rely on different ways of deterring predators.

This isn’t to say that vegetables are bad for you, but rather to challenge the idea that any type of diet can be created of foods that are “100% good.”

In reality, all foods are a mixture of good and bad. There are pros and cons for every type of food that we put in our mouths. The challenge then becomes not finding which foods are inherently bad and good and adjusting our eating habits to strictly conform to that ideal, but to focus on eating the foods that instead are “mostly good.”

Whenever you find a study that might change your behavior, you should ask yourself these questions:

- Is this an observational study or a controlled one? (i.e. one in which the experimenters made a good effort to test for one specific variable by using a randomized population, double-blind, placebo, etc.)

- If it is a controlled study, how much of the literature currently agrees with it?

- Who funded the study? As much as we like to think that science is completely objective, the fact is it doesn’t get done unless someone is paying for it. When, say, a large pharmaceutical company is paying a lot of money for you to study the effects of blood cholesterol, like it or not you’ll feel more compelled to suggest in conclusion that your study implies a need for medication.

Scientific studies are an essential way to test out observations, but they can often go horribly wrong, taking down all those who are certain of their truth in the process.

Self-Experimentation–The Ultimate Judge

The last and most important step in finding out what works for you, diet- and exercise-wise, is self-experimentation. And it is here where this admittedly rambling and esoteric article finally resolves itself into an actionable philosophy for you to take on yourself.

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter what has been observed, or what has been tested in a large population.

You need to know what works for YOU.

If you are allergic to eggs, or fish, or nuts, you shouldn’t eat them NO MATTER HOW MUCH scientific evidence there is to back up their healthfulness.

Similarly, if you can eat a few Big Macs every day and stay lean, energetic, and active, then by god you should continue eating them!

You need to test things out on yourself, trying them for at least 28 days, before you pass judgement on whether they work for you or not.

There are literally an infinite amount of things you can test, so how do you know where to start? Easy, start with what observational and clinical studies suggest works best for human beings.

And what is that? Well, in short:

- Eat lots of meat and vegetables. Eat some eggs, fruit, nuts, and seeds. Maybe even grains, dairy, and legumes. Avoid heavily-processed foods.

- Start exercising. It doesn’t really matter what you do at first. Once you make general physical activity a habit, you can become more efficient by focusing on compound movements, full-body workouts, and high-intensity exercises.

- Reduce stress levels. Sleep longer. Socialize more. Hell, even quit your shitty job if you need to.

Putting It All Together

The idea that there are magic bullets that will help everyone look and feel better is complete nonsense.

Instead, you should focus on big wins: the habits of naturally healthy people that have been further validated by scientific study.

At this point, you can intelligently experiment with different dietary plans, physical activities, and relaxation strategies that have already been suggested to work for other people.

But ultimately, it doesn’t matter what works for some culture halfway across the globe. It doesn’t even matter what works in a highly-controlled scientific study. It only matters what works for you as an individual. (Even if you can’t then generalize this to say that what works for you should work for everyone else.)

These three things–observation, isolation, and self-experimentaion–all have their flaws. They all have a level of uncertainty inherent to them. But by embracing this rather than dogmatically following a specific method, you can get the best of all three worlds.

And that’s what REALLY matters.

I'm a science geek, food lover, and wannabe surfer.

I'm a science geek, food lover, and wannabe surfer.

{ 4 comments }

I like it. A nice, simple, realistic approach.

Eat better. Move smarter. Relax harder.

It should probably be the headline of your site!

Darrin,

I agree that all foods aren’t 100% good or bad, but there are clearly better choices than others. For example, it’s evident that fruits and veggies are better for your health than highly processed baked goods. But this doesn’t mean if all you eat are fruits and veggies, your health will be perfect and if all you eat are processed foods your health is doomed. The human body is extremely complex and there are way too many factors influencing your overall health. Having said that, the more freqently we make better decisions regarding our health, the less we leave to chance. In the end, I think that’s really the best we can do.

Alykhan

@Dave

Maybe… We’ll see if it catches on!

@Alykhan:

It’s definitely not an easy task, but if anyone’s up to it, they’ll definitely be able to reap some great benefits.

@Alykhan

Very true. I’ll be honest that I’ve been a little too hardcore about diet stuff in my past, and I’d never suggest that anyone follow any regimen TOO tightly. It’s a good paradigm shift to stop looking for “magic bullets” and instead focus on the “big wins.”

Comments on this entry are closed.